Freezing rain is one of the most critical weather phenomena affecting the performance, safety, and economics of modern wind farms, especially in cold-climate regions. When supercooled raindrops strike exposed surfaces such as wind turbine blades, they freeze on contact and form a dense, transparent layer of ice known as glaze ice. Unlike light rime ice, glaze ice is heavy, highly adhesive, and capable of dramatically altering the aerodynamics and loading of the turbine.

How Freezing Rain Forms

Freezing rain typically occurs in association with warm fronts and temperature inversions. Snowflakes generated in a cold upper layer of the atmosphere fall into a warmer layer and melt into liquid droplets. As these droplets continue to fall, they pass through a shallow layer of sub-zero air near the ground. The droplets become supercooled: they remain liquid, but at temperatures below 0 °C. When these supercooled droplets impact a turbine blade, tower, or nacelle, they freeze instantly and form a smooth ice coating.

The severity of a freezing-rain event is governed by several parameters:

- Liquid Water Content (LWC) – the mass of liquid water per unit volume of air; higher LWC leads to faster accretion.

- Mean Volumetric Diameter (MVD) – the average droplet size; larger droplets have more inertia and more easily reach the blade surface.

- Air Temperature – controls whether the ice is hard and brittle or wet and partially melted.

- Relative Wind Speed – determines the droplet impact velocity and the total flux of water to the surface.

Aerodynamic Consequences for Wind Turbines

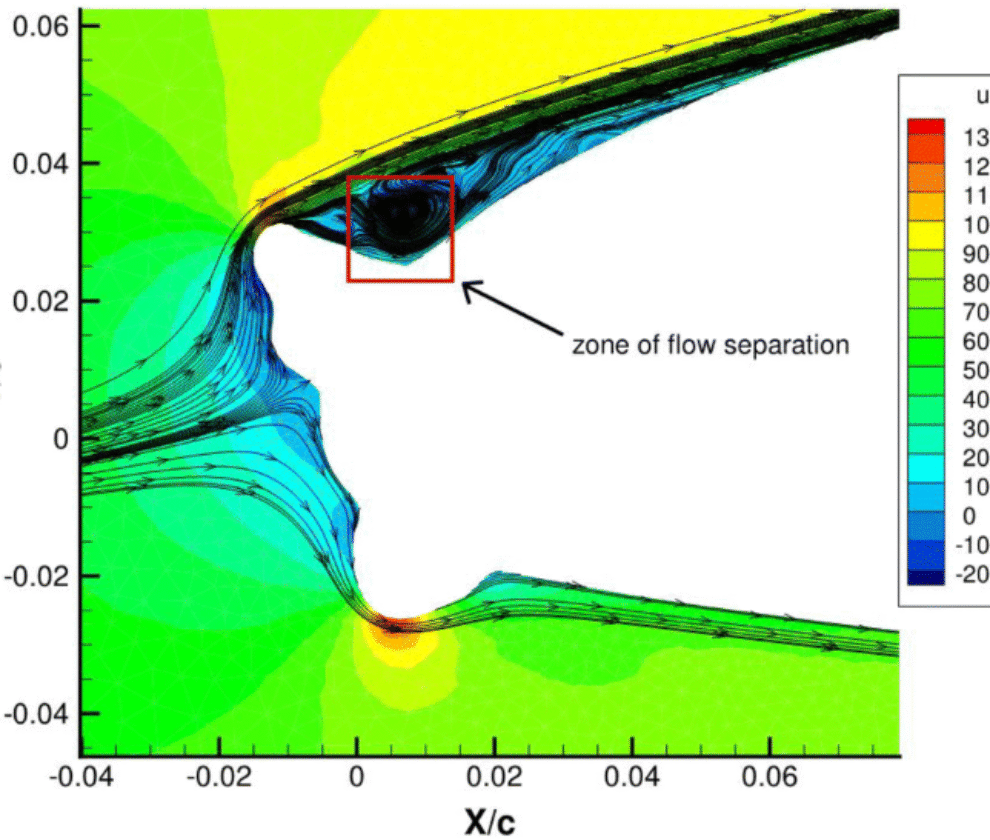

Wind turbine blades are carefully designed to operate as efficient airfoils. When glaze ice accumulates along the leading edge and suction side of the blade, it changes the local geometry and surface roughness. This has several direct aerodynamic consequences:

- Reduced lift – the wing section produces less lifting force for a given wind speed and pitch angle.

- Increased drag – rough, irregular ice shapes increase resistance to the airflow.

- Premature flow separation – the boundary layer breaks away earlier, causing stall and loss of control margin.

As a result, the actual turbine power output during icing events can drop far below the expected power curve. In severe cases, production losses of more than 50–80 % have been reported during prolonged freezing-rain episodes.

Structural Loads and Rotor Imbalance

Ice accretion is rarely uniform along the span and among the three blades. Local variations in thickness and density lead to rotor imbalance, which in turn increases vibrations and dynamic loads on the drivetrain, tower, and blade roots. These additional loads may:

- Accelerate fatigue damage in structural components,

- Trigger automatic shutdowns from vibration or overspeed protection systems,

- Increase maintenance requirements and unscheduled downtime.

In extreme cases, partial shedding of ice can generate transient loads and impact forces on the blades and nacelle, further challenging the structural design.

Safety Risks: Ice Throw and Site Access

Freezing rain not only affects energy production but also introduces safety hazards. Detaching ice fragments can be thrown significant distances from rotating blades, posing risks to service technicians, nearby infrastructure, livestock, and the public. A single chunk of ice may weigh hundreds of grams and impact the ground with enough energy to cause serious damage or injury.

For this reason, many wind farms adopt conservative operational strategies:

- Shutting down turbines during severe freezing-rain events,

- Restricting access to the turbine vicinity,

- Using ice-detection systems to monitor risk levels in real time.

Mitigation Strategies

Several approaches are used to mitigate the impact of freezing rain on wind turbines:

- Active systems such as electrical heating, hot air circulation, or microwave de-icing that melt ice directly but require significant energy and complex hardware.

- Operational strategies including predictive shutdowns based on weather forecasts and icing alarms to protect components from overload.

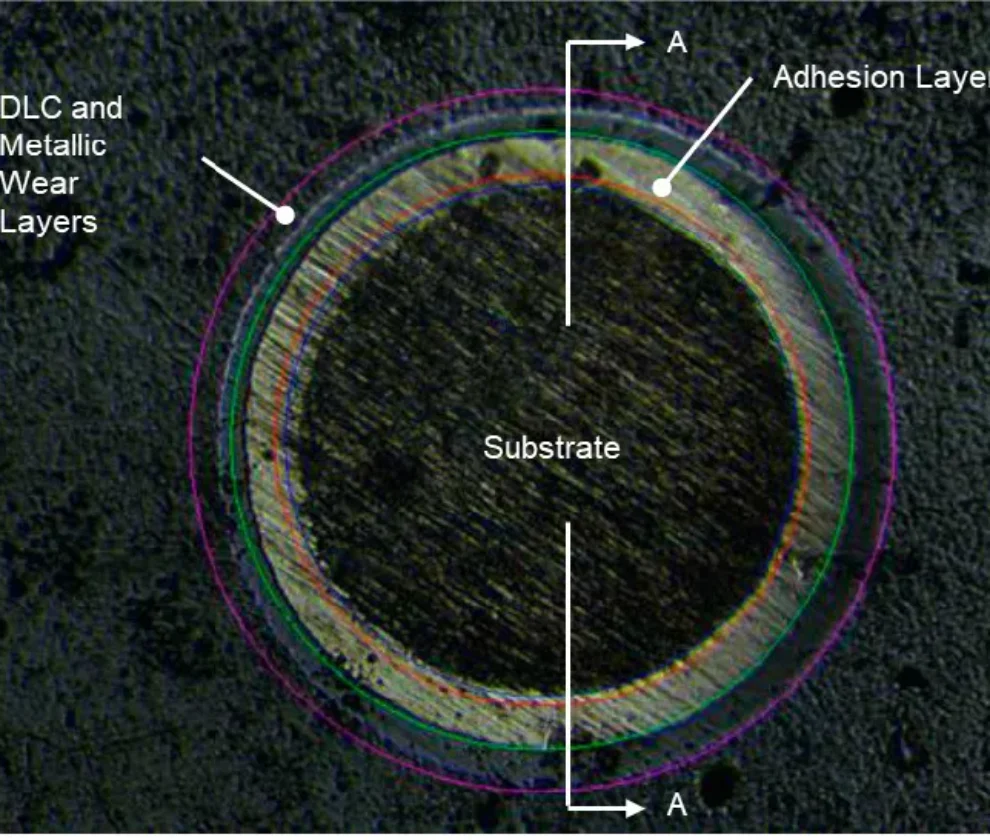

- Passive solutions such as icephobic and hydrophobic coatings that reduce ice adhesion and facilitate shedding with lower energy input.

Among these, durable icephobic coatings offer a promising balance between performance, complexity, and cost. By minimizing adhesion strength and altering surface chemistry and microstructure, such coatings aim to reduce both ice buildup and the effort required to remove it.

Conclusion

Understanding the physics of freezing rain and its effects on wind turbine behavior is essential for reliable operation in cold climates. Accurate characterization of environmental conditions, combined with robust mitigation strategies and advanced surface technologies, can significantly reduce energy losses, structural damage, and safety risks. As wind energy continues to expand into northern regions, freezing-rain–resilient design and coating solutions will become an increasingly important area of innovation.