Numerical Modeling of Ice Accretion Using CFD Methods

Accurate prediction of ice accretion on wind turbine blades is essential for designing reliable anti-icing strategies, optimizing coating thickness, and estimating energy losses in cold climates. While field measurements and icing wind tunnel tests provide valuable data, they are expensive and limited to specific conditions. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods offer a powerful complementary approach, enabling engineers to simulate complex airflow–droplet–surface interactions over a wide range of scenarios.

Fundamentals of Ice Accretion Modeling

Most modern icing models are based on an energy and mass balance at the blade surface. In simplified form, the local ice mass growth rate can be expressed as a function of:

- Liquid water content and droplet flux in the incoming air,

- Collection efficiency (fraction of droplets that actually impact the surface),

- Sticking and freezing efficiencies,

- Heat transfer, including convection, conduction, and latent heat release.

CFD is used to solve the airflow around the blade, track droplet trajectories, and compute these efficiency factors for each point on the surface. The resulting ice shape is then grown stepwise in time, and the geometry can be updated to account for the modified airfoil contour.

Airflow and Droplet Trajectory Simulation

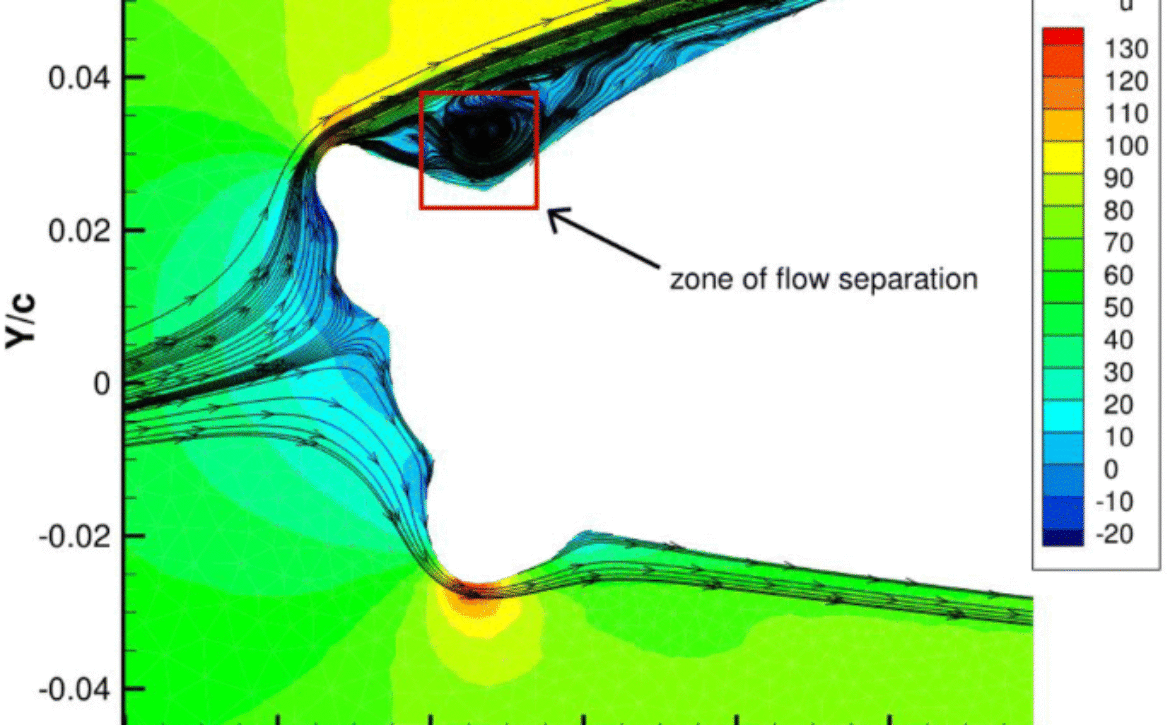

The first step in a CFD-based icing study is to compute the steady or transient airflow around the clean blade profile using the Navier–Stokes equations, often in a Reynolds-averaged form. Turbulence models such as k–ω SST are widely employed for external aerodynamic flows. Once the flow field is obtained, supercooled water droplets are introduced as a dispersed phase.

Two primary approaches are used:

- Lagrangian tracking – individual droplet paths are calculated by integrating particle equations of motion, accounting for drag and gravity.

- Eulerian methods – the droplet phase is treated as a continuum, which is more efficient for high concentrations but less detailed.

From these simulations, engineers derive the collection efficiency, which describes the fraction of droplets that impact each surface element compared to a theoretical maximum. This parameter strongly depends on droplet size, local curvature of the blade, and flow velocity.

Thermal Balance and Ice Growth

After determining where droplets strike the surface, a local thermal balance is applied. The energy released by freezing, convective heat transfer from the air, conduction within the blade and coating, and potential heating from active systems are considered. If the net balance is negative (sufficient cooling), a portion of the impinging water freezes and contributes to ice growth. If not, some water may run back along the surface before freezing downstream, leading to characteristic horn or double-horn ice shapes.

By marching forward in time, the model builds a three-dimensional ice geometry. The updated surface can then be re-meshed and used for a new CFD solution to study the aerodynamic consequences of icing.

CFD Tools and Coupled Workflows

Several specialized software tools and workflows exist for ice accretion modeling. In many projects, general-purpose CFD solvers are coupled with in-house or commercial icing modules. Typical workflow steps include:

- Generate a 2D airfoil or 3D blade geometry and computational mesh.

- Run clean-surface CFD simulations for the relevant wind speeds and angles of attack.

- Simulate droplet trajectories and compute collection efficiencies.

- Solve the surface energy balance and grow ice for a specified time interval.

- Update the geometry and repeat as needed to capture long icing events.

- Post-process aerodynamic coefficients (lift, drag, moment) and load changes.

Role of Coatings and Surface Roughness

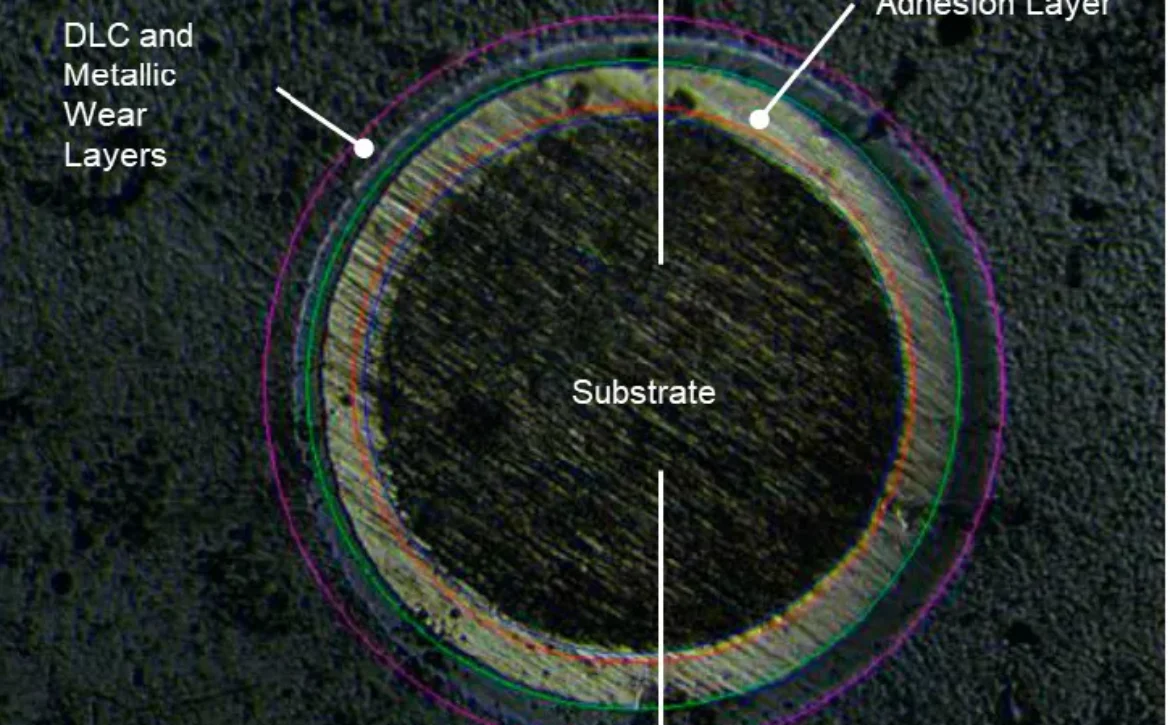

Surface coatings influence ice accretion by altering both thermal and interfacial boundary conditions. Icephobic coatings, for example, reduce the sticking efficiency and change the wetting behavior of the surface, which may promote earlier shedding or runback. In CFD models, these effects can be represented through modified boundary parameters such as:

- Reduced adhesion and accretion efficiencies,

- Different roughness heights and equivalent sandgrain parameters,

- Adjusted thermal conductivity and surface emissivity.

Accurate calibration of these parameters requires laboratory measurements and, ideally, field validation. Once implemented, CFD can be used to compare candidate coatings and optimize thickness distributions along the span.

Sensitivity Studies and Design Insights

One of the major advantages of CFD-based icing simulations is the ability to perform systematic sensitivity analyses. Engineers can vary:

- Wind speed and direction,

- Temperature and atmospheric profiles,

- LWC and MVD of the cloud or freezing rain,

- Blade pitch and rotor speed,

- Coating properties and application patterns.

These studies reveal which regions of the blade are most vulnerable to icing, how operational strategies influence accretion, and where protective coatings or heating elements are most effective. They also provide critical input for structural load calculations and control system design.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite their strengths, CFD icing models still involve simplifications. Small-scale roughness is often parameterized rather than fully resolved, and transition between laminar and turbulent flow can be difficult to predict accurately under iced conditions. Additionally, modeling partial shedding, crack formation within the ice layer, and complex mixed-phase precipitation remains challenging.

Future work is moving toward:

- Higher-fidelity multiphase simulations,

- Coupling CFD with structural and control-system models,

- Data assimilation using field measurements and machine learning,

- Detailed representation of coating behavior and aging over time.

Conclusion

Numerical modeling of ice accretion using CFD methods has become an indispensable tool for the design and operation of wind turbines in cold climates. By capturing the complex interplay between airflow, droplets, thermal processes, and surface properties, these models support better decisions on blade geometry, coating selection, and anti-icing strategies. When combined with experimental testing and real-world monitoring, CFD provides a powerful foundation for developing resilient, high-performance wind energy systems.